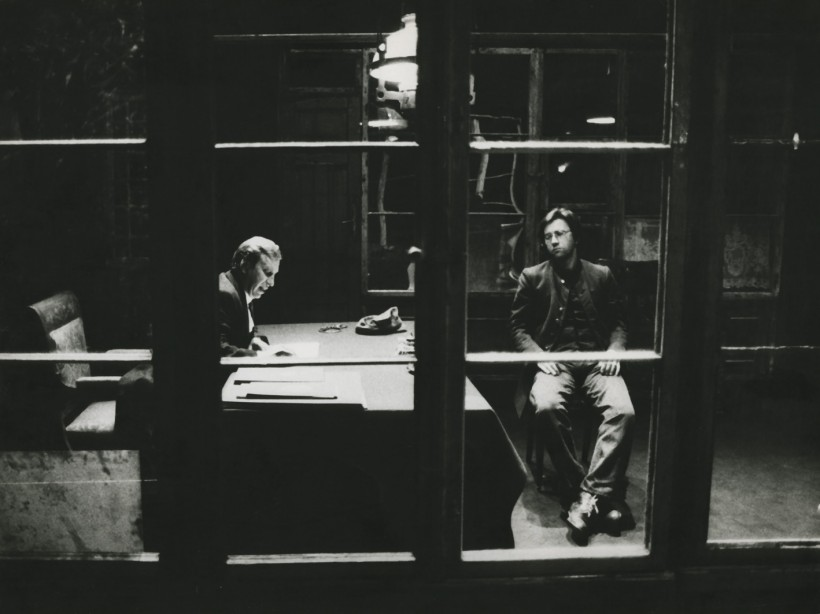

(from the left) Jerzy Stuhr (as Porfiry) and Jerzy Radziwiłowicz (as Raskolnikov). Crime and Punishment Directed by Andrzej Wajda. Stary Teatr im. Heleny Modrzejewskiej, Kraków. Photo: Stanisław Markowski

By Andrzej Wajda

Translated from Polish by Magda Romanska

Translator’s Introduction: Decolonizing Dostoyevsky?

Andrzej Wajda (1926-2016), Oscar-winning, legendary Polish theatre and film director is considered one of the most prominent figures in Polish cinema and one of the most influential filmmakers of the twentieth century. Wajda’s career spanned over six decades, during which he directed over forthy feature films, numerous documentaries, television dramas, and theatre shows. Wajda was a member of the Polish Film School, a group of filmmakers who emerged in the late 1950s and early 1960s whose work focused on psychologically complex situations, human emotions, and choices made in extreme circumstances. He was best known for his war trilogy consisting of the films A Generation (1955), Kanal (1957), and Ashes and Diamonds (1958), which explored the experiences of Poles, particularly Polish Underground Army (Armia Krajowa) during World War II and the post-war period. Wajda’s films often dealt with social and political themes, and moral and political dilemmas faced by Poles and Polish fighters caught in a double bind of Nazi and Soviet occupations.

Not many people know that in addition to his prolific career as a filmmaker, Wajda was also a renowned theater director who directed productions at some of the most prestigious theaters in Poland, including the Stary Teatr in Kraków, the Teatr Powszechny in Warsaw, and the Teatr Współczesny in Wrocław. Wajda’s approach to theatre was known for its elaborate psychology, moody and somber mis-en-scéne, and heightened tension. Wajda directed his own adaptation of Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s novel Crime and Punishment in 1984 at the Stary Teatr im. Heleny Modrzejewskiej, in Kraków.[1] However, this was not Wajda’s first encounter with Dostoyevsky; in 1971, at the same theatre, he directed Demons, adapted for stage by Albert Camus. [2] That staging was inspired by Pushkin and Japanese theatre. In 1977, Wajda also directed Nastazja Filipowna, based on Dostoyevsky’s Idiot. The Dostoyevsky trilogy is considered a cornerstone of Wajda’s theatre, and it’s often referred to as the Theatre of Conscience.[3]

After successful run at Stary Teatre, Wajda’s adaptation of Crime and Punishment was performed at theaters throughout Europe and the United States. The show was praised for its compelling visual imagery, minimalist staging and the use of light and shadow in exploration of the psychological and philosophical themes of Dostoyevsky’s novel. Stylistically richer than the 1984 theatre version, the 1987 TV version was included in the top hundred theatre productions recorded by Polish television.[4] The adaptation was considered one of the most significant productions of the novel in modern times and a landmark of Polish theater. It contributed to Wajda’s image as a visionary director in both film and theater, solidifying his reputation as one of the leading theater directors of his generation.

Dostoyevsky’s novel, exploring the commandment ‘Thou Shalt Not Kill,’ follows the story of Rodion Raskolnikov, a poor student in Saint Petersburg who kills an old woman, a ruthless pawnbroker. He justifies the murder by a higher moral purpose: stealing a woman’s money would allow him to escape poverty and go off to accomplish great deeds for humanity. After the murder, however, Raskolnikov is wracked with guilt and struggles to maintain the convictions he relied on to commit the murder. To cover up the crime, he further kills the pawnbroker’s sister, a kind, innocent, and mentally challenged Lizaveta.

Wajda’s adaptation is structured around the power struggle between the main character, Raskolnikov and his interrogator, the detective Porfiry Petrovich, who is investigating the murders. The dramaturgical framing of the adaptation focuses on the dialogue between the two men: “It is a battle of two protagonists, who in three long conversations, ‘have something to take care of.’”[5] In the program note to the production, Wajda included a fragment from Bakhtin’s text about the importance of Dostoyevsky’s dialogue:

[T]he center of Dostoyevsky’s artistic world must lie dialogue, and dialogue not as a means but as an end in itself. Dialogue here is not the threshold to action, it is the action itself. It is not a means for revealing, for bringing to the surface the already ready-made character of a person; no, in dialogue a person not only shows himself outwardly, but he becomes for the first time that which he is—and, we repeat, not only for others but for himself as well. To be means to communicate dialogically.[6]

Characters in Dostoyevsky’s novels exist, Bakhtin argues, only through dialogue. In that way, by focusing on the dialogue between Raskolnikov and Porfiry Petrovich, Wajda wanted to distill the novel to its philosophical essence.

Despite the narrow focus of the adaptation, the critics observed that the production was faithful to the spirit and thematic elements of Dostoyevsky’s novel. The astute examination of guilt, redemption, and moral responsibility was praised for its profound insights into the intricate workings of the human psyche. In addition to moral dimension of the story, however, Wajda was also interested in a psychological power game between Raskolnikov and Porfiry.[7] The set, sparce, dirty, and decrepit gave an impression that we’re peeking into forbidden domain, someone’s soul.[8] It blurred the line between audience and fictional space suggesting, as one critic pointed out, that potential pitfalls for anyone who would venture into Raskolnikov’s moral universe.[9] The actors, Jerzy Radziwiłowicz and Jerzy Stuhr, titans of Polish film and theatre, received praise for their skillful portrayal of the two characters, with nuanced and commanding presence.

Radziwiłowicz’s Raskolnikov tries very hard to hide his crimes, but his body language, facial tics and tone of voice gives him away. Despite trying his best, he is unable to control them. This portrayal was contrasted with Stuhr’s aloof interpretation of Porfiry, who as one of the critics noted, plays with Raskolnikov like a cat plays with a mouse without revealing much of who he is himself. There is emptiness behind Porfiry’s mask, and Stuhr fills it by becoming Raskolnikov’s alter ego: “He is able to trap Raskolnikov because he knows his thoughts and feelings, and he knows them because they are his own.”[10]

Porfiry empathizes with Raskolnikov’s belief in his own intellectual superiority and moral right to do whatever he wants for his own benefit. This makes Porfiry absolutely in control of the situation: “Raskolnikov’s experiment conducted on his own selfhood to answer the question about the limits of freedom and morality becomes for Porfiry a tasty morsel, like for a vulture, which he consumes slowly and methodically, eating up the entrails of his victim in order to reach the heart.” [11] Another Polish critic, however, concluded that such interpretation of Porfiry’s role was not effective as it overwhelmed the production, and overshadowed the figure of Raskolnikov himself: we seem to learn more about the detective than we do about the criminal.[12] Yet another critic pointed out that Porfiry’s sadistic treatment of others, from which he seems to derive some sort of pleasure, is contrasted with Raskolnikov’s cerebral, premedicated violence which he justifies intellectually but does not fundamentally enjoy. As far as that argument goes, Porfiry seems to be a better reflection of modern world, the critic notes.[13]

Like the novel, the adaptation asks the Machivellian question whether “the end justifies the means,” whether “a grand vision can justify a murder.”[14] Writing about Dostoyevsky’s book, Wajda pointed out that it is a novel about ideological murder: “Raskolnikov hates people. Rejected and humiliated by his poverty, he nonetheless feels superior to everyone else. That is why in his article about the crime, he gives moral permission to certain individuals to spill the blood of others!”[15] To narrow down the large book, Wajda was inspired by Hamlet’s ironic lines: “I must be cruel to be kind,” focusing on the argument made by Raskolnikov to not just excuse his repulsive act but to make it, in fact, morally right. What is most fascinating and gruesome about Dostoyvesky’s novel, Wajda writes, is not the description of the murder itself, but the verbal duel between the murderer and his investigator.

Crime and Punishment is a novel about the crime of ideals and in that way, it reflects the murderous ideologies of the twentieth century, Wajda wrote: “How well I know this argument! – he wrote – From Nazi’s concentration camps to the newest political murders. All of them have been justified by the ‘permission to take blood’ – if needed (no longer even just when necessary) for the glorious progress of the humankind.”[16] Unlike most crime novels, Crime and Punishment doesn’t ask who killed, but why.

In the program of the production, Wajda also included 1957 essay by Stanisław Mackiewicz which considers Crime and Punishment a form of religious novel:

Dostoyevsky wanted to be a Russian writer, but he became a world’s writer because the problem of his novel is a religious problem. Dostoyevsky arrogantly asks whether the rules of religious morality should truly be followed and then, repentant, concludes that, yes, they should. The commandment ‘Thou shall not kill’ can be lost in the chaos and arguments of the day that often deafen its meaning, but then, a new form of mysticism emerges, and without words, silently, but strongly makes all of us understand that murder for higher purpose cannot be, that it is nonsense, stupidity, sin. (translation from Polish mine).[17]

Wajda felt that as an adaptor, he had a moral responsibility towards Polish society to illustrate that fundamental moral core of Dostoyevsky’s novel.[18] Polish critic Ryszard Przybylski noted that “Wajda saw in Dostoyevsky’s work a vision of the collapse of the civilization of reason, which he himself wanted to build in the past. It was a vision of the world in which people who are incapable of distinguishing between good and evil began to kill each other due to their vanity and sense of impunity.”[19]

As of now, there hasn’t been any publication dealing with Andrzej Wajda as a theatre writer. Although he is well-known in the film and theatre world, scholars and students have not been able to access his texts and adaptations. This adaptation provides a glimpse into Wajda’s process and the structure of his dramatic writing. This translation was commissioned by the Polish Institute in New York a couple of years ago for the retrospective of Wajda’s films. It is based on the TV version of the show presented at the event.[20]

Publishing the adaptation of Dostoyevsky’s novel today, however, is fraught with one’s own moral struggle. After Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Eastern European intellectuals and academics who research and write about Russian literature, particularly those living in the West, had to face a reckoning with the current state of Slavic studies and scholarship. Focused mostly on Russian literature and culture, Slavic departments across the landscape of Western universities continue to teach it from an imperial Russian perspective: “Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has led to widespread calls for the reassessment and transformation of Russo-centric relationships of power and hierarchy both in the region and in how we study it.”[21] Although there have been a few attempts to analyze the imperialism of Dostoyevsky’s political writings, most of Slavic and Russian literary studies have focused, as Wajda’s adaptation, on the psychological and moral, not political, dimension of his novels. But as Olga Maiorova noted in her essay on Dostoyevsky and the empire, “Empire-building was not only history for Dostoyevsky and his contemporaries, it was the reality in which they lived.”[22] Like most of his compatriots, Dostoyevsky supported the imperial project, embraced the Raskolnikovian sense of superiority towards the conquered nations, and wrote extensively about the virtues of Russia’s civilizing mission.[23]

Elif Batuman, writing in The New Yorker’s 2023 article, “Rereading Russian Classics in the Shadow of the Ukraine War,” about her own struggle how to approach Russian literature post 2022 invasion, notes: “It was explained to me that nobody in Ukraine wanted to think about Dostoyevsky at the moment, because his novels contained the same expansionist rhetoric as was used in propaganda justifying Russian military aggression. My immediate reaction to this idea was to bracket it off as an understandable by-product of war—as not ‘objective.’”[24] Ukrainian writer, Victoria Amelina, who was killed when the Russian rocket struck a café she was in, wrote: “The debate on boycotting Russian culture is not what western artistic and intellectual circles should be worrying about now. At least not if they have anything to do with Europe and its values of human rights, dignity and solidarity.”[25]

Rather than trying to rethink Russian literature, the more urgent project of the moment is to preserve and promote Ukrainian culture and literature, which is being systematically destroyed. It is easy to make an argument that there should be, if not a boycott, at least a temporary pause on studying and writing about Russian literature until the literary field can rethink and reinvent some new, decolonizing approach, which would contextualize it in a proper historical and political framework. That was my first impulse, too.

Yet, I chose to publish the translation of Wajda’s vision of Dostoyevsky right now not so much as an artifact of Russian culture, but as an artifact of Polish culture, a legacy of a colonized society struggling to reconcile the many facets of its oppressor. Staged in 1984, only four years after the Martial Law was established in Poland, and only a year after it was lifted (from 13 December 1981 to 22 July 1983), Wajda’s adaptation was a tacit commentary on Polish-Russian relations. During the Martial Law, the Polish society pondered with trepidation whether the Russian army would enter Poland and if so, what would their invasion entail. Wajda’s adaptation of Crime and Punishment was not a rare event in Polish theatre after World War II. In fact, it was considered an obligatory reading in Polish society of that time. Many other well-known Polish directors before Wajda and after Wajda attempted to adapt the novel.[26] It is one of the reasons why Wajda’s version could focus on selected scenes and didn’t have to worry about the audience understanding the entire novel: every spectator would have had read it. Having grown up in Poland, I read it for the first time, in Polish, in high school. Polish fascination with Dostoyevsky’s novels wasn’t just part of the colonial project of Russification that we endured under Soviet occupation, which included obligatory learning of the Russian language. It was, in many ways, an attempt, to understand and grasp the workings of the Russian psyche. It was, I think, a survival strategy, a struggle of the subalterns to deconstruct and understand their colonizers.

There is dissonance in Wajda’s work that reflects this struggle. In his theatrical treatment of Dostoyevsky’s writing, Wajda considers him an international writer, avoiding any references to Russia or Dostoyevsky’s imperial sympathies. In Wajda’s films, however, Russia and Russians loom large as violent barbarians, whose psychology, Wajda sometimes seems to suggest, cannot be grasped; it is simple, guided by greed and sadistic, mindless impulse. While these references were often veiled in the movies made before 1989, in Wajda’s later work, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, he becomes more open about his view of Russians. In his last film about the Warsaw Uprising, The Crowned-Eagle Ring (Pierścionek z orłem w koronie), released in 1992, a young and virginal girlfriend of the Polish partisan fighter, Wisia, is taken and brutally gang raped by a group of Russian soldiers. She is left shell-shocked and broken by the trauma. Such, accurate, portrayal of Soviet ‘liberation’ of Poland reflected the image of the civilizational divide between the Polish and Russian societies, particularly its men. In later years, the theme of Russian barbarism returns. One of Wajda’s last movies, 2017 Katyń, is a historical drama about the 1940 mass execution of nearly 22,000 of Polish officers by the Soviet army.

How can the nation which produced Crime and Punishment, be so immersed in the centuries old brutal project of colonial conquest and so unaware of its implications? Which is the ‘true’ Russia? Which is the ‘true’ Dostoyevsky? For many Central and Eastern Europeans who grew up reading Russian literature, coming to terms with its legacy is a personal project. Wajda’s adaptation is an artifact of a particular historical moment in Polish history and culture, reflecting the tragedy of Central and Eastern European countries struggling to find and hold on to their national identities while also compulsively trying, over and over again, to understand its oppressor. This adaptation, when properly understood, is a form of Polish and by extension, Central and Eastern European artifact of its colonial history.

Crime and Punishment continues to be staged in Poland, with the same, now postcolonial, urgency to comprehend the oppressor through the prism of its most prominent writer, as if somehow Dostoyevsky’s novels could provide a clue, could unlock the secret to who Russians are and what to do with them. 2023 production at Polish Theatre in the Underground in Wroclaw (Polski Teatr w Podziemiu), entitled literally, Crime and Punishment, Because of Russian Crimes Which We Can’t Understand (Zbrodnia i Kara. Z powodu zbrodni Rosjan, których nie potrafimy zrozumieć) weaves in the passages of the novel with documentary text taken from the various investigations of Russia’s genocidal and war crimes against the Ukrainians.[27] Today, the name Dostoyevsky has become permanently tied to Russia’s genocidal violence. Nobel Peace Prize winner, Oleksandra Matviichuk, speaking at the 2023 Warsaw Forum put it succinctly: “Russian culture for me is not ballet or Dostoevsky, it’s about the bodies of dead civilians left in the streets by their troops. From Syria to Ukraine they think they can do whatever they want and impunity has become part of Russia’s culture.”[28] Like Raskolnikov…

Magda Romanska is Professor of Theatre and Media at Emerson College, Boston, MA, Faculty Associate at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard, and a Principal Researcher at metaLAB (at) Harvard. She is the author of five critically acclaimed scholarly books, including The Post-traumatic Theatre of Grotowski and Kantor (2012); TheaterMachine: Tadeusz Kantor in Context (2020); Reader in Comedy: An Anthology of Theory and Criticism (2016); and The Routledge Companion to Dramaturgy. She translated five plays from Polish of Boguslaw Schaeffer, and published, Boguslaw Schaeffer: An Anthology (2012). Romanska’s scholarly research has received awards from the Polish Studies Association and the American Society for Theatre Research. As a playwright, she is a recipient of the MacDowell Fellowship, the Mass Council Artist Fellowship for Dramatic Writing, the Apothetae and Lark Theatre Playwriting Fellowship from the Time Warner Foundation, and PAHA Creative Arts Prize. She has taught at Harvard University, Yale School of Drama, and Cornell University.

[1] “Zbrodnia i kara. Production History.” Encyklopedia Teatru Polskiego, https://encyklopediateatru.pl/przedstawienie/7622/zbrodnia-i-kara Accessed 6 Aug. 2023.

[2] “Biesy. Production History.” Encyklopedia Teatru Polskiego, https://encyklopediateatru.pl/przedstawienie/9967/biesy Accessed 6 Aug. 2023.

[3] Maciej Karpiński,(1989). Dostoyevsky: Theater of Conscience: Three Stagings by Andrzej Wajda at the Stary Theater in Krakow. Publishing Institute Pax.

[4] “Zbrodnia i kara. Production History.” Encyklopedia Teatru Polskiego, https://encyklopediateatru.pl/przedstawienie/7622/zbrodnia-i-kara Accessed 6 Aug. 2023.

[5] Jacek Cieślak. “Tragedie ludzi i ich sumień.” [Tragedies of People and Their Conscience]. Rzeczpospolita. No. 238. October 11, 2016. https://encyklopediateatru.pl/artykuly/229845/tragedie-ludzi-i-ich-sumien Accessed 6 Aug. 2023.

[6] Michail Bakhtin (1984). “Discourse in Dostoevsky”. Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics. Ed. Emerson, C., & Booth, W. C. University of Minnesota Press. Pp. 252.

[7] Dorota Krzywicka. “Zbrodnia i kara.” [Crime and Punishment] Echo Krakowa. No. 25. February 5, 1985. https://encyklopediateatru.pl/artykuly/45865/zbrodnia-i-kara Accessed 6 Aug. 2023.

[8] Jan Bończa-Szabłowski. “Szaleństwo Raskolnikowa.” [The Madness of Raskolnikov]. Rzeczpospolita online. May 14, 2010. https://encyklopediateatru.pl/artykuly/94152/krakow-zbrodnia-i-kara-wajdy-w-tvp-kultura Accessed 6 Aug. 2023.

[9] Kazimierz Kania. “Sceniczny rachunek Raskolnikowa i Wajdy.” [Scenic Reckoning of Raskolnikov and Wajda]. Kierunki. No 48. November 25, 1984. https://encyklopediateatru.pl/artykuly/46209/sceniczny-rachunek-raskolnikowa-i-wajdy Accessed 6 Aug. 2023.

[10] Jerzy Niecikowski. “Alter ego Roskolnikova.” [Raskolnikov’s Alter Ego]. Film. No. 22. May 31, 1987. https://encyklopediateatru.pl/artykuly/45975/alter-ego-raskolnikowa Accessed 6 Aug. 2023.

[11] Krzysztof Miklaszewski. “Syndrom Raskolnikowa.” [Raskolnikov’s Syndrom]. Dziennik Polski. No 254. October 26, 1984. https://encyklopediateatru.pl/artykuly/46213/syndrom-raskolnikowa Accessed 6 Aug. 2023.

[12] Olgierd Jędrzejczyk. “Zbrodnia i kara’ bez Raskolnikowa?” [‘Crime and Punishment’ Without Raskolnikov?]. Gazeta Krakowska. No. 242. October 9, 1984. https://encyklopediateatru.pl/artykuly/45863/zbrodnia-i-kara-bez-raskolnikowa Accessed 6 Aug. 2023.

[13] Andrzej Wajda. “Zbrodnia i kara w inscenizacjach Andrzeja Wajdy.” [‘Crime and Punishment’ According to Wajda]. Tygodnik Powszechny. October 21, 1984. https://encyklopediateatru.pl/artykuly/46094/zbrodnia-i-kara-w-inscenizacjach-andrzeja-wajdy Accessed 6 Aug. 2023.

[14] Jan Bończa-Szabłowski. “Szaleństwo Raskolnikowa.” [The Madness of Raskolnikov]. Rzeczpospolita online. May 14, 2010. https://encyklopediateatru.pl/artykuly/94152/krakow-zbrodnia-i-kara-wajdy-w-tvp-kultura Accessed 6 Aug. 2023.

[15] Andrzej Wajda. “Zbrodnia i kara.” Teatr. No 10. October 1, 1987. https://encyklopediateatru.pl/artykuly/46029/zbrodnia-i-kara Accessed 6 Aug. 2023.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Program. Crime and Punishment, premier 7 October 1984. https://encyklopediateatru.pl/repository/performance_file/2016_10/80421_zbrodnia_i_kara__stary_teatr__krakow__1984.pdf

[18] Andrzej Wajda. “Zbrodnia i kara.” Teatr. No 10. October 1, 1987. https://encyklopediateatru.pl/artykuly/46029/zbrodnia-i-kara Accessed 6 Aug. 2023.

[19] Krzysztof Miklaszewski. “Syndrom Raskolnikowa.”[Raskolnikov’s Syndrom]. Dziennik Polski. No 254. October 26, 1984. https://encyklopediateatru.pl/artykuly/46213/syndrom-raskolnikowa Accessed 6 Aug. 2023.

[20] The film is available at: https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=244634197437383 Accessed 6 Aug. 2023.

[21] Todd Prince, “Moscow’s Invasion of Ukraine Triggers ‘Soul-Searching’ at Western Universities As Scholars Rethink Russian Studies,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Published Jan. 1st, 2023, https://www.rferl.org/a/russia-war-ukraine-western-academia/32201630.html?

[22] Olga Maiorova, “Empire,” in Dostyoevsky in Context, ed. Deborah A. Martinsen and Olga Maiorova, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

[23] See Razvan Ungureanu, “Russian Imperial Presence in Literature.” Published April 3, 2007, http://www.ruf.rice.edu/~sarmatia/407/272ungure.html; Volodymyr Yermolenko, “From Pushkin to Putin: Russion literature’s imperial ideology,” Published June 27, 2022, https://www.tbsnews.net/thoughts/pushkin-putin-russian-literatures-imperial-ideology-447998. And “Yes, the Russian literary canon is tainted by imperialism,” Published October 6, 2022. https://www.economist.com/culture/2022/10/06/yes-the-russian-literary-canon-is-tainted-by-imperialism

[24] Elif Batuman, “Rereading Russian Classics in the Shadow of the Ukraine War,” The New Yorker, January 23, 2023, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2023/01/30/rereading-russian-classics-in-the-shadow-of-the-ukraine-war

[25] Amelina Victoria, “Cancel Culture vs. Execute Culture: Why Russian Manuscripts don’t burn, but Ukrainian manuscripts burn all too well,” Pen Ukraine, Published April 1, 2022. https://pen.org.ua/en/cancel-culture-vs-execute-culture-why-russian-manuscripts-don-t-burn-but-ukrainian-manuscripts-burn-all-too-well

[26] “Zbrodnia i kara. Production History.” Encyklopedia Teatru Polskiego, https://encyklopediateatru.pl/przedstawienie/7622/zbrodnia-i-kara Accessed 6 Aug. 2023.

[27] https://www.teatrpolskiwpodziemiu.pl/pl/spektakle/zbrodnia-kara

[28] Oleksandra Matviichuk, Warsaw Forum 2023. https://twitter.com/MatteoPugliese/status/1709557128694825411

Crime and Punishment

By Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Adapted and Directed by Andrzej Wajda

Translated from Polish by Magda Romanska

Reprinted with permission by the Polish Institute in New York which commissioned the translation.

CHARACTERS

Porfiry Petrovich (Порфирий Петрович)

Rodion Romanovich Raskolnikov

Sofia Semyonovna Marmeladova (Russian: Софья Семёновна Мармеладова), variously called Sonia and Sonechka

Polunya, Sonia’s sister

Alexander Grigorievich Zamyotov (Александр Григорьевич Заметов)

Dmitri Prokofich Razumikhin (Дмитрий Прокофьич Разумихин)

Mikolka – Nikolai Dementiev (Николай Дементьев)

Mieszczynin

Koch

Proch

SCENE I

“You’re the Murderer”

MIESZCZYNIN: Murderer . . . Murderer . . . .

RASKOLNIKOV: What are you talking about? Who’s the murderer?

MIESCZYNIN: You’re the murderer . . . Murderer . . .

SCENE 2

“Koch’s Testimony”

KOCH: I was going to see Alyona Ivanovna. We had a meeting scheduled. I was standing in front of her door. I rang once, twice, but there was no answer. I pulled at the handle, ten times in a row. Nothing. Alyona Ivanovna – I yelled – you old hag – nothing. Lizavieta – nothing. No answer. I rang ten times, nothing. Then someone behind me called: ‘Good morning, Mr. Koch’ – because my name is Koch.

PORFIRY: What?

KOCH: Koch.

PORFIRY: Koch . . . Koch . . .

KOCH: Nobody’s there? What the hell do I know.

How do you know me?

He says: ‘Not too long ago, in “Gamrymusie,” I won three rounds against you at billiards.’

I say: ‘Aha . . . . ’

‘Wait’ – he screamed as I began to pull at the door again – ‘Look, there is a slit in the door when you pull it’ – he says.

‘So what?’ – I asked.

‘You don’t understand! It means that one of them is home. If both of them were out, they would have closed the door on the outside, with the key, and not on the inside, with the bolt. It’s clear.

Either both of them fainted or . . . ’

And then, I understood. He ran downstairs and I stayed by the door.

I rang gently and then, I carefully touched the doorknob, pulling and pushing it slowly.

Then, I looked into the keyhole, but I couldn’t see anything. The key was stuck inside. I got scared and ran downstairs. We were going up when we passed the two screaming painters . . .

PORFIRY: Painters . . .

KOCH Mikolka and Witka. When we got up, the door to the apartment was open. The two bodies, Alyona’s and Lizavieta’s, were lying there in a pool of blood.

/walks over/

If I have stayed there – he would have burst out and killed me with an ax.

SCENE III

“Article about the Crime”

RAZUMIKHIN AND RASKOLNIKOV IN THE BACKGROUND LAUGHING

RAZUMIKHIN: By the way, Rodya, you’re a pig.

RASKOLNIKOV: What are you ashamed of? Romeo! Just wait, when I tell the story to everyone, haha!

RAZUMIKHIN: Listen, listen, listen, this thing with Dunia, it’s serious. . . . I, brother . . . Eh . . . What a pig you are!

RASKOLNIKOV: Just look at you. You all cleaned up, nails and hair, and all! Haha!

RAZUMIKHIN: Pig!!! Not a word about it here, or . . . I’ll break your head! /breaks the glass/ Shit!

PORFIRY: There is no need to destroy furniture, Gentlemen. It’s a loss to our national wealth.

RASKOLNIKOV: I apologize. My name is Raskolnikov . . .

PORFIRY: Not at all, the pleasure’s all mine. You both came here looking all happy . . . What? He won’t even say hello?

RASKOLNIKOV: I just told him he resembles Romeo . . . Haha!

RAZUMIKHIN: Pig!

PORFIRY: He must have had a good reason if one word made him so angry.

RAZUMIKHIN: You, what’s that to you, Detective? That’s it! Ok, let’s get to the point.

Here’s my friend, Rodion Romanovich Raskolnikov. For one thing, he has heard a lot about you and wanted to meet you. Two, he has a little favor to ask you. Zamiotov? You’re still here?

RASKOLNIKOV: I’ve heard you questioned the owners of valuables pawned with Alyona Ivanovna. She had something of mine as well. Nothing expensive, just a ring I got from my sister. She gave it to me as a goodbye present before I left for Petersburg. And my father’s silver watch. These things aren’t worth much, maybe five, six rubles, that’s all. But for me, they have a sentimental value.

What should I do now? I don’t want these items to get lost, especially my father’s watch.

It is the only thing I have left of him. My mother will be crestfallen if it’s sold. Women!

PORFIRY: What? Ah! This is what you should do:

You should go to the police and tell them that you have learned about this murder, and you would like to inform the prosecutor that these valuables belong to you, and you would like to buy them back. There should be no problem.

RASKOLNIKOV: Yes, it’s just . . . I . . . I don’t have much money now . . . not even to buy back such cheap items . . . . I would like to . . . right now, I would like to just inform you that these things are mine and if only I had some money . . .

PORFIRY: It doesn’t matter. You know what? Why don’t you write me a letter: ‘Learning about the murder, etc., etc., I would like to officially inform you that there are two items I pawned which I would like to’ . . . etc.

RASKOLNIV: On regular paper?

PORFIRY: Sure! The most regular you can find!

RASKOLNIKOV: I’m really sorry to bother you with such silly things, but I got really worried when I heard . . .

RAZUMIKHIN: Rodia! So, that is why you looked so scared yesterday when I told you that Porfiry is investigating the owners who pawned their things with Alyona?

RASKOLNIKOV: I told you this watch is the only memento I have of my father. You can laugh all you want to.

PORFIRY: Hold on, hold on, hold on . . . . These things of yours cannot get lost. Anyway, I have been waiting for you.

RAZUMIKHIN: What? You’ve been waiting? You knew he pawned his things there as well?

PORFIRY: Both of your items . . . what was that? The ring and the watch were there wrapped in paper on which she clearly wrote your name and the date when you brought the things.

RASKOLNIKOV: You’re very perceptive . . . . I’m just saying, there are probably a lot of other owners . . . a lot of people who pawned their things . . . . It would be hard to remember everyone. And you, on the contrary, you remember all of them . . . and . . .

PORFIRY: We know almost all of them now. Actually, you are the only one we’ve been waiting for.

RASKOLNIV: I’ve been a bit sick lately.

PORFIRY: Yes, that’s what I’ve heard. I’ve also heard you were incredibly irritable of late. Now, you’re pale.

RASKOLNIKOV: I am not pale. . . . No! I am completely healthy now.

RAZUMIKHIN: “Completely healthy.” That’s a good one. Just yesterday, he was nearly hallucinating with fever. . . . Can you believe this Porfiry? He could barely stand on his own two feet, but when I turned around, he quickly got dressed and sneaked out of the apartment. He wandered somewhere all alone until midnight, in a complete daze. I repeat – i n a c o m p l e t e d a z e!

RASKOLNIKOV: Bullshit! Believe me! Never mind, you won’t believe me anyway!

RAZUMIKHIN: Rodia! Would you be leaving your apartment if you weren’t nearly unconscious?

RASKOLNIKOV: I’m really sorry. We’ve been bothering you with such trivialities for half an hour now. You’ve had enough of us, right?

PORFIRY: Not at all. If you only knew how interested I am in you. Yes, I’m very curious, watching, listening . . . Well, after yesterday’s party, my head is exploding . . . and generally, I feel like crap.

RAZUMIKHIN: What? Something interesting happened? I had to leave at the most interesting moment. Who won?

ZAMIOTOV: But nobody, of course.

RAZUMIKHIN: Imagine, Rodia, what topic they were discussing yesterday: does crime exist or not? I’m telling you. We laughed out loud.

RASKOLNIKOV: No wonder. Just the same old social nonsense.

PORFIRY: That’s not how the question was formulated.

RAZUMIKHIN: Not quite, that’s true. We began with Socialists: ‘crime is just a protest against unjust social order, and nothing more.’ No other reasons were given, and nothing . . .

PORFIRY: Ah. . . . You got things all mixed up!

RAZUMIKHIN: N-nothing else! . . .

PORFIRY: Just look at you, how you’re getting carried away. I agree, the social environment plays a significant part, I agree to that.

RAZUMIKHIN: If you want, I can prove it to you now that your eyebrows are gray, based solely on the fact that Ivan the Great was six feet tall, and I’ll prove it clearly, progressively, and with a liberal slant. I can bet you I can prove it.

ZAMIOTOV: I accept! Listen, Gentlemen, how he goes about it.

RAZUMIKHIN: Hell, are you kidding me? It’s not worth talking to you, Mr. Detective . . . All your wisdom about the crime is based on one thing only: money. Prior to the crime, the man was poor as dirt and suddenly, he’s a big spender. Where did his money come from? Eh, anyone who wants can play you like a child.

ZAMIOTOV: Well, the fact is they all are the same. He commits a cleaver murder, betting his life on one horse, and minutes later, he lets himself be caught at the local bar. Always, but always, they are caught spending money like crazy. Not everyone is as smart as you. And you? You wouldn’t go to the bar?

RASKOLNIKOV: No. I wouldn’t. I would do it like this: I would take the money and the valuables, and I would go straight to a secluded place that I’d found earlier, some abandoned garden or something like that. I would pick a big heavy rock, and I would hide both the money and the valuables under it. Later, I wouldn’t touch it for one year, two, or maybe even three years. And you, you can search all you want.

ZAMIATOV: You’re crazy!

PORFIRY: No, no, no. A very clever idea!

RAZUMIKHIN: Be careful. He’s doing it all on purpose. You don’t know him! Yesterday, he came to their side, just to fool them.

RASKOLNIKOV: You’re really such a good actor?

PORFIRY: What do you think? Be careful, or I’ll fool you as well. No, no, seriously now. Let’s talk about your sociological divagations on crime. I’m thinking about the article you wrote . . . about crime . . . or something like that, I don’t remember the title. I read it two months ago in the journal ‘Periodic Word.’

RASKOLNIKOV: My article? In ‘Periodic Word’? Right, indeed, about six months ago, after I left the university, I wrote an article. It was influenced by a book. But, I dropped it off at the ‘Weekly Word’ not the ‘Periodic Word.’

PORFIRY: Well, it ended up at the ‘Periodic Word.’

RASKOLNIKOV: But ‘Weekly Word’ ceased to exist. That’s why they didn’t print it then.

PORFIRY: ‘Weekly Word’ merged with ‘Periodic Word.’ That’s why your article was printed just two months ago in ‘Periodic Word.’ Here you go . . . your article . . . you can take a look. . . . You didn’t know it was published? You live in such seclusion, you’re unaware of things that directly pertain to you.

RAZUMIKHIN: Bravo, Rodia! I didn’t know either! Let me read it!

RASKOLNIKOV: How did you know it was my article? I signed it with my initial only.

PORFIRY: The editor-in-chief told me two weeks ago. He’s also very interested in you.

RASKOLNIKOV: If I remember it right, I analyzed the psychological condition of a criminal at the moment he commits murder.

PORFIRY: Yes, yes, yes, exactly. You also stressed that the crime is always followed by illness. Very, very original thought, but . . . I’m actually interested not in this part of the article, but in something else, one thought you included at the end . . . not a very clear one. . . . If you remember, you suggested that there is a group of people, who can – no, not just ‘can’– they ‘have the right’ to commit the worst crimes imaginable because they are above the law.

RAZUMIKHIN: What? What? The right to commit a crime? But not because: ‘It’s the fault of the society. The society influences the individual, etc.’?

PORFIRY: No, not at all. According to your article, Raskolnikov, people can be divided into the ‘ordinary’ and the ‘extraordinary.’ Those ‘ordinary’ ones should follow and respect the law because, as you say, they are just ‘ordinary’ people. But those ‘extraordinary’ ones can commit any crimes they want to, because they are, after all, ‘extraordinary.’ It appears it was your case as well? Ain’t it the truth?

RAZUMIKHIN: What is it? It’s impossible he wrote something like that!!

RASKOLNIKOV: No, no no! It’s not quite like that. I admit you summarized my thought well, almost exactly. . . . But, there is one difference; I don’t claim that the ‘extraordinary’ people are obliged to commit all possible crimes – as you suggest. I think that if this was what I actually claimed, they would not print my article. I only mentioned that the ‘extraordinary’ individual has a right . . . maybe not a legal right . . . but a moral right, in his conscience only, to cross certain moral laws, and only if he has some higher ideals he strives for that would justify it.

Sometimes, maybe even salvation for all humanity.

You pointed out that my article wasn’t quite clear. Let me clarify it for you, assuming that is what you want.

Here you go.

If the discoveries made by Kepler and Newton, due to some extraordinary circumstances, could not have been made but for the death of one man, or maybe ten hundred men, who stood in their way, Newton would be justified – even obliged – to . . . get rid of them, if that’s what was necessary to make his discoveries known. . . . But, it does not mean that Newton would have a right to kill anyone he liked, or steal everyday whatever he wanted.

Furthermore, if I remember it right, I point out in my article that everyone . . . All of those whom we consider the founders and first lawgivers of humanity – starting with antiquity, through Lycurgus, Solomon and Mahomet, to Napoleon, etc. etc. – they all, without exception, could be considered criminals just because, by creating new laws, they had to break the old ones. The old laws that were given by tradition and their fathers. They also never shied away from spilling blood, if only it would help them. It is interesting to think that those beacons of humanity, lawmakers and founders, were often the cruelest ones. I argue that everyone – not only the great ones – but normal people who are somewhat special, who could say or create something new, extraordinary even, those people, just because of who they are and what they could do, could be considered criminal.

Otherwise, they would never emerge from the crowd, never get unstuck from the banality of their lives. And their nature would never, ever allow them to remain stuck. I would even add that they have an obligation, a responsibility not to let it happen.

As you can see, I’m not claiming anything new. These points were written and printed hundreds of times before. I admit, my separation of people into ‘ordinary’ and ‘extraordinary’ is somewhat loose, but I’m not hung up on exact numbers. I do believe in my main thesis: according to the laws of nature, people can be generally divided into two categories: the lowest ones, who are, so to speak, raw material. Their only job is to procreate. The second group is the people proper. They have some kind of talent or skill which allows them to stand above the crowd and pronounce N E W W O R D. The first group, the raw material, are by nature submissive and they like it that way. I believe they should be submissive because that’s what they were made for. There is nothing humiliating or disrespectful about it.

People who belong to the second group, they all break the law. They are the lawbreakers because they can and should do it.

Their crimes are relative and varied. Most often they destroy the existing status quo for a higher better order. If such an extraordinary man needs to step over bodies, if he needs to draw some blood to accomplish his task, I think, he should, internally, and in peace with his conscience, allow himself such a march through blood, to overcome any moral obstacles. It depends, of course, on his ideals and their range. Those are the circumstances I talk about in my article when I write about ‘the right to crime.’

But there is of course, nothing to worry about because the slums will not allow for the extraordinary to raise. They will cut them down. But of course, the next generation picks them up and puts them on a pedestal. The ‘ordinary’ ones are the masters of the present, but the ‘extraordinary’ ones are the masters of the future. The first group procreates and keeps us as we are. The second group pushes the world forward toward well-defined goals. But everyone in my theory has a right to equality. Vive la guerre eternelle, until the Judgment Day, that is.

PORFIRY: Well, well. So you believe in Judgment Day, after all?

RASKOLNIKOV: Yes, I do.

PORFIRY: And . . . do you believe in God? I’m sorry if that’s too personal.

RASKOLNIKOV: Yes.

PORFIRY: And in the raising of Lazarus?

RASKOLNIKOV: Yes. Why do you ask such questions?

PORFIRY: Do you believe in it literally?

RASKOLNIKOV: Literally.

PORFIRY: Aha . . . Never mind that. Let’s go back to our discussion. You know, sometimes those ‘extraordinary’ ones survive. On the contrary, sometimes, they . . . .

RASKOLNIKOV: They triumph during their lifetimes? Oh yes, some accomplish their goals in their lifetime, and then . . .

PORFIRY: Then, they themselves begin to cut down the others?

RASKOLNIKOV: If such a need arises, and you know, that’s almost always the case. That’s a very clever point.

PORFIRY: Thank you.

Could you tell me how we should distinguish between the ‘ordinary’ and ‘extraordinary’ folk?

Maybe there are some signs when they are born?

You know, it would be helpful to be more detailed here, especially about the outward signs. Forgive my concerns, the concerns of a practical and law-abiding man. Could we, for example, have them wear some kind of uniform, or maybe some emblems, or mark them somehow?

Because I have to admit, if there is a confusion, if a man of the lower class gets it into his head that he belongs to the other group, and goes all the way out to remove these ‘moral obstacles’ as you called it . . .

RASKOLNIKOV: That happens very often. And, by the way, this observation of yours is even more clever than the last one . . . .

PORFIRY: Thank you very much . . .

RASKOLNIKOV: You’re welcome. Could you take under consideration, though, that such a mistake is dangerous only if made by the ‘lower classes’?

Regardless of their innate subservience, and due to certain stubbornness that even cows have sometimes, there might be a large group of such people who would like to see themselves as the ‘destroyers’ of the old world order, who bring in the ‘new word.’

And they would do it faithfully convinced that they are right. It seems to me though that there is no real danger on their part since they don’t have the guts to go too far.

They can be chastised for their overzealousness once in a while to remind them of their proper place, but nothing more. Nothing else will have to be done because eventually, they’ll chastise themselves, or each other. . . . They’ll even feel compelled to do it in public because it looks appropriate and pedagogical. In other words, you shouldn’t be concerned about this at all. . . . That’s the law of nature.

PORFIRY: Well, you calmed some of my fears. That’s for sure. But, I have one more concern.

Could you tell me: how many of those ‘extraordinary’ ones who can kill all others are there? Of course, I’m willing to bow down to your idea, but you understand that I feel a bit uneasy, if there are going to be a lot of them. What do you say?

RASKOLNIKOV: In regards to this issue, you shouldn’t worry. People who can claim any new thought, some talent or skill, well, there aren’t that many of them born out there. I don’t know what law there is, but there must some kind of law of nature, that we will know one day, a law that directs all of that. The human mass, mingling together, once in a while can bring forth one man who is extraordinary. One in a hundred thousands. Geniuses – there might be one in millions. Great geniuses – cream of the crop of humanity – maybe one in a hundred millions. I don’t know how we would know who they are, but I stand by my point: there is and has to be a special law for them. There can be no accidents here.

RAZUMIKHIN: Are you kidding? You’re fooling around, aren’t you? You can’t be serious. Talk, talk, one bullshitting the other.

Rodia, brother, you’re not being serious? If you’re serious . . . then you might be right that there is nothing new in this. It reminds me of other things I’ve heard or read before. Nonetheless, Rodia, there’s something o r i g i n a l in it, something – and this thought really horrifies me – that something that belongs only to you . . . that would allow for murder in a c c o r d a n c e w i t h o n e’s c o n s c i e n c e, and forgive me, Rodia, with such fanaticism . . .

So that is the main thought of your article.

Such permission to murder in a c c o r d a n c e w i t h o n e’s c o n s c i e n c e . . . I believe, it is worse than if you would legalize it by official means . . .

PORFIRY: Yes! It is worse.

RAZUMIKHIN: No. You just got carried away! One cannot think like that . . . I have to read your article again.

RASKOLNIKOV: I didn’t write all that in the article. I only mentioned it briefly.

PORFIRY: Yes, yes, yes, yes. Now, I know exactly how you feel about the crime. I have to say, you calmed my fears a bit about the accidental mix-up between the two classes, but I have one more question. Let’s assume that some young man gets it into his head that he’s Lycurgus or Mahomet . . . and . . . he goes ahead and starts to remove the ‘moral obstacles.’ Here’s an example: I’m planning a long trip. To be able to do that, I need money . . . a lot of money . . . so what do I do?

RASKOLNIKOV: That’s unavoidable. Stupid and vain people often fall into a trap like that, especially if they’re young.

PORFIRY: That’s right. What then?

RASKOLNIKOV: ‘Nothing.’ What happens then is not my fault or my worry. That’s just the way the world is, always was and always will be. Razumikhin just said that I condone murder. So what? The society is well-protected by police, detectives, courts, prisons, gulags. You have the power to find and punish the criminal.

PORFIRY: Yes, indeed . . . And when we find him? What then?

RASKOLNIKOV: He deserves what he’ll get.

PORFIRY: Yes, that’s a healthy logic. What about his conscience?

RASKOLNIKOV: What’s that to you?

PORFIRY: Oh, it’s just my sense of humanity.

RASKOLNIKOV: Whoever has a conscience, let him suffer, once he realizes his wrongdoings. It’ll be his punishment.

PORFIRY: Don’t be offended, but I need to ask you one more question. I want to ponder one small tiny little idea . . . . Just so I wouldn’t forget about it later . . . .

RASKOLNIKOV: Sure, tell me about your small idea.

PORFIRY: You see, my small idea . . . is . . . how to put it . . . a bit flirtatious . . . psychologically. When you were writing your article, you must have considered yourself one of those ‘extraordinary’ men, bringing the ‘new word’ – as you put it . . .

RASKOLNIKOV: That’s a possibility.

PORFIRY: If you felt this way, is it possible that you could decide yourself that you were justified in committing a murder?

RASKOLNIKOV: Even if I’d crossed that line, I wouldn’t have told you about it.

PORFIRY: No, no. I’m just . . . interested in your opinion, trying to understand your article better, from a literary point of view.

RASKOLNIKOV: You should have realized by now that I don’t consider myself to be Mahomet or Napoleon . . . or anyone like them . . . so, I am unable to give you a proper answer since I don’t know how I would have behaved if I considered myself to be like them.

PORFIRY: Hey, hey, my dear, who in today’s Russia does not think he’s Napoleon?

ZAMIOTOV: What? Maybe one of such Napoleons killed our Alyona Ivanovna?

PORFIRY: What? You’re leaving already? What a pity. We were having such a nice talk. . . . It was a pleasure to meet you. . . . About your jewelry, just write me a letter, like I said. Or, you know what . . . why don’t you drop by my office again soon . . . maybe even tomorrow? I’ll be here around eleven, for sure. We’ll take care of everything . . . we’ll talk . . . . You’re one of the last ones who were in their apartment. Maybe you can help us . . . .

RASKOLNIKOV: Do you intend to interrogate me officially?

PORFIRY: You misunderstood me. As you see, I’m very meticulous, and I talk to everyone. You, as the last person . . .

Wait, wait, I just remembered something! You were the one bugging me the other day about this guy, Mikolka. I know he’s innocent, but I had to talk to him anyway . . .

Let me ask: you were there at eight o’clock, right?

RASKOLNIKOV: Eight.

PORFIRY: When you were going up the stairs, at eight o’clock, did you happen to see two painters on the second floor? They were working with the door opened in one of the apartments? It’s very important for them . . . !

RASKOLNIKOV: Painters? No, I didn’t see them. I don’t remember. I didn’t even notice any opened apartments . . . . But on the fourth floor, indeed, I remember some office worker was moving out from his apartment . . . located right across from Alyona’s . . . I remember this clearly . . .

The soldiers were removing his couch and they pushed me to the wall . . . . But painters . . . . No, I don’t remember . . . and an opened apartment . . . no. . . . I’m sure there were no opened apartments.

RAZUMIKHIN: Porfiry! What are you talking about! The painters were there on the day of murder and Rodia was there three days earlier! Why do you even ask him such questions?

PORFIRY: Shit! Crap! I got all mixed up. Too much work. We really need to know if someone didn’t see them there at eight o’clock. I got everything mixed up! Shit!

RASKOLNIKOV: You might try to focus more.

SCENE IV

“Streetwalker”

/Sonia and Koch/

KOCH: I had a meeting with Alyona scheduled.

I rang the bell once, twice, but nobody opened. I rang again . . . ten times maybe. Then someone called: ‘Mr. Koch’ – because my name is Koch. Nobody’s there. What the hell do I know. How do you know me?

He says: ‘Not too long ago, in “Gamrymusie,” I won three rounds against you at billards.’

I say: ‘Aha. . . . ’

‘Wait’ – he screamed as I began to pull at the door again – ‘Look there is a slit in the door when you pull it’ – he says.

‘So what?’ – I asked.

‘You don’t understand! It means that one of them is home . . . ’

SCENE V

“Mieszczynin’s Testimony”

MIESZCZYNIN: I asked – ‘What do you want?’

He didn’t answer, just pulled the doorbell.

‘Who are you ?’ – I asked.

‘What do you want?’

‘I want to rent an apartment – I am just looking around.’

Who rents apartments at night?

‘I see the floor is all cleaned up. No more blood. Are you going to paint it?’

‘What blood?’ – I asked.

‘The old hag and her sisters were killed not too long ago. There was a pool of bllll-oooood here.’

‘Ok, but you are who?’ – I asked again.

‘I’m Rodion Raskolnikov. I live in the shelter, not too far away from here.

SCENE VI

“Raising of Lazarus”

/Koch and Sonia are getting dressed/

KOCH: I began to push and pull at the doorknob. We went up and the door was half-opened. The two bodies were lying on the floor, in a pool of blood.

If I had stayed there, he would have jumped out and killed me too.

/Koch gives Sonia money and exits. Raskolnikov enters/

SONIA: O my God! It’s you.

RASKOLNIKOV: It’s late, I know. Eleven already?

SONIA: Yes. The clock just struck at the neighbor’s.

RASKOLNIKOV: Why are you standing like that. Come, sit down. Your hands are so cold. Fingers like a dead person’s.

SONIA: I’ve always had such cold hands.

/Raskolnikov kisses her hand and kneels down/

What are you doing? What are you doing? Not in front of me! I’m . . . I’m a great sinner . . . without shame!

RASKOLNIKOV: I wasn’t bowing for you. I was bowing for the entire suffering humanity.

It’s true, you’re the sinner –

Your greatest sin is that you’ve lost and betrayed yourself for no purpose. It’s horrible that you live here in this squalor that you hate, and you know yourself that you are neither helping or saving anyone!

Just tell me, tell me, how such shamelessness and malice lives in you along with other, almost saintly feelings. It would be wiser and more rational just to drown yourself and get it over with!

SONIA: And what would then happen to my sister?

RASKOLNIKOV: Polunya will end up just like you!

SONIA: No. It cannot be! God won’t allow it! God will protect her!

RASKOLNIKOV: What if God doesn’t exist? And you’re praying to him so ardently, Sonia?

SONIA: What would I be without God?

RASKOLNIKOV: And what is it that God gives you?

SONIA: Be silent! Don’t ask! You don’t deserve to . . . !

RASKOLNIKOV: “That’s it! That’s it!” – I don’t deserve to . . . !

SONIA: He gives me everything!

RASKOLNIKOV: /browsing the Bible/ Where is the passage about Lazarus? About the resurrection of Lazarus? Where is it? Find it.

SONIA: You’re looking in the wrong place . . . It’s in the Gospel of John . . .

RASKOLNIKOV: Find it and read it to me –

SONIA: You never read it?

RASKOLNIKOV: A long time ago . . . in school . . .

SONIA: You didn’t hear it in church?

RASKOLNIKOV: I . . . don’t go to . . . . And you? Do you go to church often?

SONIA: N-no.

RASKOLNIKOV: I understand . . .

SONIA: I went last week . . . for the funeral . . .

RASKOLNIKOV: Whose funeral?

SONIA: Lizaveta. Someone murdered her with an ax.

RASKOLNIKOV: Were you friends with her?

SONIA: Yes . . . . She was a just woman . . . . She used to come to visit me . . . not too often . . . it wouldn’t look good. We used to read together . . . and talk. She will be talking to God face to face now.

RASKOLNIKOV: Read!

SONIA: What’s that to you? You don’t believe anyway . . . ?

RASKOLNIKOV: Read! I want you to! You’ve read with Lizaveta.

SONIA: “Now a certain man was ill, Lazarus of Bethany, the village ofMary and her sister Martha . . .”

“And many of the Jews had joined the women around Martha and Mary, to comfort them concerning their brother. Then Martha as soon as she heard that Jesus was coming . . . ”

POLYUNIA: “Then Martha as soon as she heard that Jesus was coming went and met Him, but Mary was sitting in the house. Now Martha said to Jesus, ‘Lord, if You had been here, my brother would not have died. But even now I know that whatever you ask of God, God will give You.’ Jesus said to her, ‘Your brother will rise again.’ Martha said to Him, ‘I know that he will rise again in the resurrection at the last day.’ Jesus said to her, ‘I am the resurrection and the life. He who believes in Me, though he may die, he shall live. And whoever lives and believes in Me shall never die. Jesus therefore again groaning in himself cometh to the grave. It was a cave, and a stone lay upon it. Jesus said, Take ye away the stone. Martha, the sister of him that was dead, saith unto him: Lord, by this time he stinketh: for he hath been dead four days.”

“Jesus saith unto her, Said I not unto thee, that, if thou wouldest believe, thou shouldest see the glory of God? Then they took away the stone from the place where the dead was laid. And Jesus lifted up his eyes, and said, Father, I thank thee that thou hast heard me. And I knew that thou hearest me always: but because of the people which stand by I said it, that they may believe that thou hast sent me. And when he thus had spoken, he cried with a loud voice, Lazarus, come forth. “

SONIA: That’s all about the raising of Lazarus.

RASKOLNIKOV: I need you. That’s why I’m here.

SONIA: I don’t understand.

RASKOLNIKOV: You’ll understand later. You also crossed . . . . You also wasted life . . . your own. If you stay here alone, you’ll eventually go crazy, like me. We have to walk together, on one path! Let’s go!

SONIA: Why? Why are you saying things like that?

RASKOLNIKOV: Why? Because we can’t continue like this – that’s why! Finally, you need to think bravely and seriously, and not like a child, crying and whining that God won’t allow. He has already allowed many times.

Children? Children? What’s going to happen to children? They are the image of Christ: He asked us to love – theirs is God’s Kingdom. They are the future of humanity . . .

SONIA: What ought we to do?

RASKOLNIKOV: What ought we to do? Break what’s unbreakable, once and for all. Take on yourself the suffering! Do you understand? Freedom and power, but power foremost! Power over the entire slimy anthill of humanity! . . . That’s the goal! That’s a reason.

It’s possible that I’m speaking with you for the last time.

If I don’t come tomorrow, you’ll learn about me sooner or later. If I come tomorrow, I’ll tell you who killed Lizaveta. Farewell!

SONIA: You know who killed Lizaveta?

RASKOLNIKO: Yes, yes, I know and I will tell you. Only you! I chose you a long time ago. I won’t come to ask you for redemption. I’ll just tell you. Farewell. Don’t give me your hand. Tomorrow!

SCENE VII

“Surprise”

MIESZCZYNIN: ‘What blood’ – I ask – and he starts to pull the doorbell.

PORFIRY

What? He asked about blood? Pulled the doorbell?

What a scum!

/doorbell/

What again?

Sit here. Be quiet. I might call you.

SCENE VIII

“Interrogation”

PORFIRY: Come on in, young man! Welcome, welcome . . . . Sit down brother! Oh, maybe you don’t like to be called “young man” or “brother”? I don’t intend to be disrespectful . . . . Yes, here’s the chair.

RASKOLNIKOV: I brought the letter you asked for.

PORFIRY: What letter?

RASKOLNIKOV: About the watch . . .

/Porfiry reads the letter/

Well-written?

PORFIRY: Letter, letter! Letter? Yes, yes . . . quite well. Should be sufficient.

RASKOLNIKOV: You were saying yesterday you wanted to ask me. . . . officially . . . about my acquaintance with that . . . killed woman?

PORFIRY: Yes, yes, yes! But we’re in no hurry . . . we have time, plenty of time. Cigarette?

You have yours?

You know, I’m hosting you here, and my police apartment is just around . . . . It’s all finished up. I need to make a few small renovations . . .

Such a police apartment is a good thing, what?

What do you think? A good thing?

RASKOLNIKOV: Good, indeed.

PORFIRY: Good thing, good thing, indeed.

RASKOLNIKOV: You know what?

I’ve heard that there is this investigative trick you all are obliged to follow: start with something banal, even serious, but completely unconnected to the main investigation. Once the suspect feels all safe and comfortable – Wham! – suddenly, you whack him with an unexpected question. I’ve heard that this is standard procedure, recommended by every police manual. Isn’t it?

PORFIRY: What? You think I wanted you to . . . with this apartment?

/They laugh and Porfiry throws up/

RASKOLNIKOV: You wanted me to come to see you to ask me some questions . . . . I’m here, and if you want something, ask. If you don’t, let me go. I don’t have time for this. I’m busy . . . I’m sick of all this. Do you hear me? Partially, that’s what got me sick . . .

To sum it up –

To sum it up: you either ask me or let me go . . . and if you ask me, you need to ask me formally! I’m not agreeing to anything else. So, for the moment, I’m leaving. There is nothing we can do here together.

PORFIRY: My God! Why you got so offended? But it’s all nonsense, my dear.

We have time. We have time. It’s all nonsense.

I’m welcoming you here as a guest. Forgive me, Rodion Romanovich. Your name is Rodion, is it?

I’m very stressed out. Sometimes I get completely out of control . . . I shake all over. . . . For thirty minutes . . . With my complexion, it can lead to a stroke.

Sit down, please.

Sit down, or I’ll think you’re mad at me.

I have to tell you something about myself, Rodion Romanovich.

I am, you know, a bachelor, not a very social man, rather a hermit, a finished man – do you understand – yes, I’m an island unto myself. . . .

. . . . And . . . did you notice, here, in Russia, especially in Petersburg, when you have two people, who might not know, but who respect each other, and do what you will, they can’t find a common ground. They become, so to speak, paralyzed by each other’s presence. Why does this happen? Maybe because we’re too honest and don’t want to play games with each other. What do you think?

Put away your hat. It looks like you’re about to leave. . . . Stay, I’m very happy to see you here.

I don’t dare to offer you a cup of coffee because we can’t do that here, but we can sit down for five minutes and have a friendly conversation, why not? . . . About those investigations – please, forgive me for pacing like that. I don’t want to offend you. I just need some exercise. I sit all the time, so it is nice to move around a bit . . . hemorrhoids . . . . I thought about going to a sanatorium, exercise . . . I’ve heard that the generals, they all exercise, jumping up and down . . . yes, yes . . . . That’s progress . . . in our century . . . yes. . . .

Coming back to our investigative tricks – as you put it – I have to agree with you completely.

Just think, what suspect – even the most uncouth and lowly individual – doesn’t know that he is going to be first lulled with irrelevant questions only to be hit unexpectedly with a sneaky one! You hit the bullseye with this one! So you really thought I wanted to lull you . . . ? Haha!

You’re clever! I’ll stop . . . but . . . just by association, if I’m to describe the form of this interview . . . . What is a form?

Form is all nonsense. Sometime you can just chat, like this, friendly and without a form. What is a form?

Form shouldn’t limit us each step of the way. And being a detective is a bit like being an artist . . .

You’re completely right . . . completely right to mock so cleverly our strategies.

/sits down behind the desk/

Those tricks are laughable indeed, and they don’t bring any results. They’re too tied up in formality. Yes . . . form indeed. Well! They’re talking about the coming reform of the judiciary system. Maybe we’ll have different forms now . . .

Dear Rodion Romanovich. . . . Let’s assume that I suspect someone . . . or another, or other of a crime that I’m to investigate . . .

You are studying law, Rodion Romanovich?

RASKOLNIKOV: Yes, I did.

PORFIRY: Law. Let me give you one example. Just don’t think I’m trying to teach you something, a person who writes articles about crime and law! God forbid! I wouldn’t dare. I’m just curious to know what you think . . .

Let’s assume that I have one, or two, or three suspects, why would I use any tricks on them? To forewarn and scare them away? Even if I have proof of their guilt. Of course, there are people that I simply need to arrest, but there are others as well, who have a certain character. Why not let them walk free for a while? You see? You’re laughing! People vary and we shouldn’t treat them all the same. You say, ok, what about the leads, the proof? Well, that can be a problem. But my job is to conduct the investigation carefully and precisely. I need to find such proof that would make the guilt clear, without a doubt, like two and two is four. If I make an arrest too soon, even if I myself was certain of his guilt, I might lose a chance to get the unbeatable proof.

Why? If I try to get him too soon, he’ll shut up, psychologically and literally, and I’ll never get anything out of him. He’ll understand that he is arrested.

But if I leave him roaming free – while letting him know that I’ll watch him all the time, every day, every minute, every step – he will inevitably go crazy and come to me himself, or he’ll make such a huge mistake, I’ll have no problem proving his guilt once and for all. Mathematically. A simple peasant can make a mistake, but even the most intelligent of them will make some mistake if he’s under pressure. You see, the secret is to figure out the psychology of the criminal.

Stress, stress – you need to remember about the stress. Today, everyone’s stressed out, confused, torn! . . . and bitter. How bitter they are. It’s like a goldmine. I really don’t need to worry about one or another criminal like that walking around town on the loose for a few days. Let him walk free, my poor little lamb. I know where he is and he won’t get away! Maybe abroad? Maybe if he’s Polish, but not Russian. Once he knows that I am onto him, he won’t dare to escape. Where? Maybe deeper into the country? But the country is full of peasants, those traditional, uncouth, authentic Russian peasants. The city man, modern man, he’d rather go to prison than live among them. What does it mean ‘to run away’? That’s a shallow question. He won’t run away, not only because he has no place to go, but he can’t run away from me psychologically!

Nice, isn’t it?

Have you ever seen a moth circling a candle? Like a moth, the criminal will be circling around me; he’ll lose his taste for freedom; he’ll become incoherent, confused. He will catch himself in the net, scared to death. . . . Even more: he himself will prepare for me the proof, the two-and-two-is-four certainty . . . . He’ll be circling and circling around that light, closer and closer, until WHAM! Right into my mouth he’ll fall and I’ll swallow him whole. That’s going to be pure pleasure.

What?! What?! You don’t believe me? You still think I’m just playing some innocent tricks? Yes?!

Of course, you’re right. God gave me a posture that provokes laughter, doesn’t it? I am right, but I have an open mind. Isn’t it true as well? I’m giving you all this confidential information, without asking for anything.

What? What happened?

You can’t breathe? Maybe I should open the window?

/he leans forward in his chair and looks at Raskolnikov carefully/

RASKOLNIKOV: No, don’t bother. There is no need.

I can see clearly now that you suspect me of this murder. I have to tell you I’m completely fed up with this. If you think you can pursue me legally, please, do so. Arrest me. But, torturing and mocking me like that, I won’t allow.

I won’t allow it!

Do you hear it? Porfiry Petrovich? I won’t allow it!

PORFIRY: Calm down!!!

RASKOLNIKOV: I won’t allow it!

PORFIRY: Calm down!! Someone will hear you! They’ll come here and what’ll we tell them?

What? Are you ok?

You need some fresh air.

Some water, my dear, you need some water.

/running/

A little panic attack!

My dear, drink it up. Maybe it’ll help. . . .

/Raskolnikov pushes away the glass./

It was just a little panic attack, Radion Romanovich! My dear! You should take better care of yourself. You can go mad if you don’t.

You can get seriously ill.

You should know, I know about something else. I know you went back to her apartment, pulled the doorbell, asked about the blood . . . . You see – I know everything . . .

Sit down, my lovely, sit down, for God’s sake.

Sit down.

It’s not good, not good, if a man can’t avoid the temptation to pull the doorbell, ask about the blood. I know psychology. Sometimes, you have this desire to jump out the window. Sometimes, strangely, it is a tempting . . .

Sickness, hallucinations! Daze! From the beginning to the end, terrible fever and daze . . .

RAKOLNIKOV: No! No! No! I wasn’t in a daze! I wasn’t hallucinating! It was real! I was conscious! Do you hear me?

PORFIRY: I hear you. I hear everything, whatever you’re saying. But, Rodion Romanovich, my friend, have some mercy on me. If you were in any way connected to this murder, why would you claim that you did it while conscious and not in a daze or fever?

Just tell me, is it logical? Is it logical? On the contrary, if you felt guilty in any way, you would try to convince me that you were in a daze, unconscious, sick, unable to judge. Maybe not?

RASKOLNIKOV: You’re lying. You want to prove to me that you saw through my game, that you’re able to predict everything I’d say.

You’re lying. You want to scare me . . . or you just mock me . . .

You know very well that the best defense for the killer is to tell the truth, to tell the truth whenever possible. I don’t believe you.

PORFIRY: You don’t believe me? This is some kind of obsession of yours. You don’t believe me? You don’t believe me? Well, you do believe me in part, and soon you’ll believe me completely. And you know why? Because I like you and I honestly have your best interest in mind. I repeat – Doorbell . . . such a jewel, such an important piece of information. I give it to you and it doesn’t mean anything to you? You’ve lost your good sense and can’t see clearly.

RASKOLNIKOV: You’re lying. I don’t know what for, but you’re lying . . . . You just said something completely different . . . . I can’t be mistaken . . . . You’re lying!

PORFIRY: Am I? Am I lying . . . . Well, why then, I, the detective, tell you how to defend yourself: “illness, daze, hallucination, past suffering.”

RASKOLNIKOV: All right, all right. Tell me then. Do you officially believe me to be free from suspicions? Tell me, now! Once and definitively!

PORFIRY: Don’t shout! Be quiet!

Why do you want to know? Why do you want to know so much if so far, nobody even touched you!

Mister, why do you insist so much?

RASKOLNIKOV: I repeat, I won’t tolerate this any longer!

PORFIRY: What? Uncertainty?

RASKOLNIKOV: Don’t be such a snake. I don’t want to . . . . Do you hear me? I won’t . . . I won’t and I don’t want to . . . . Do you hear me!

PORFIRY: But be quiet, be quiet! I’m serious right now! I’m not joking! Be quiet.

RASKOLNIKOV: I won’t let you torture me like that!

Arrest me, search me, ok. But you need to follow the legal procedures. Don’t play with me! Don’t you dare play with me . . .

PORFIRY: And I invited him as a friend . . .

RASKOLNIKOV: I don’t need your friendship. I spit on it! Do you hear me? That’s it. I’m grabbing my hat and leaving.

Do you want to arrest me?

/Raskolnikov is about to leave/

PORFIRY: And you don’t want to see the surprise?

RASKOLNIKOV: What surprise?

PORFIRY: Behind the door. It’s closed. Here’s the key!

RASKOLNIKOV: You scumbag. You’re lying! You want me to slip and betray myself . . .

PORFIRY: But you can’t betray yourself more than you already did. You are mad. Fact. Don’t scream or I’ll call the policemen.

RASKOLNIKOV: Call, call, call all you want! Nothing will happen! You knew I’m ill. You wanted to drive me mad so I would betray myself. But it’s all a joke. Show me the proof. I understand everything now. You don’t have a thing, except your suspicions! . . . You know my character, who I am. You wanted to drive me crazy, knock me off with your tricks . . . . Bring your delegates. What are you waiting for? What are you waiting for? Go on!

PORFIRY: What delegates? Are you hallucinating again?

RASKOLNIKOV: They’re coming! You sent for them . . . . You waited for them! You calculated it . . . go on! Bring them all! Delegates, witnesses, whoever you want . . . bring them all. I am ready, I’m ready! . . .

SCENE IX

“I am the killer”

PORFIRY: What?

PROCH: We have brought the arrested, Mikolka!

MIKOLKA: I am guilty! My sin! I’m the killer! I am guilty! My sin! I’m the killer!

I am guilty! My sin! I’m the killer!

PORFIRY: Mikolka, what are you saying?

MIKOLKA: /On his knees/ I am . . . the killer . . .

PORFIRY: Who did you kill?

MIKOLKA: Alyona Ivanovna and her sister, Lizaveta Ivanovna. I killed them . . . with an ax. I think it was madness, or something . . .

PORFIRY: What nonsense? What madness? Did I ask you if you were mad or sane? Come here! Who did you kill?

MIKOLKA: Alyona Ivanovna.

PORFIRY: How did you kill her?

MIKOLKA: With an ax. I took it with me.

PORFIRY: By yourself?

MIKOLKA: By myself. Mitka is innocent. He didn’t help me with anything.

PORFIRY: Mitka – innocent? The porter saw both of you?

MIKOLKA: Because I . . . just . . . wanted to . . . confuse everyone . . . that’s why I ran with Mitka the other day.

PORFIRY: You’re repeating someone else’s words. My apologies, Rodion Romanovich! You can go now . . . . See, what surprises . . . what surprises . . . who would have known! Well! Well!

RASKOLNIKOV: You didn’t expect this? Did you?

/They face each other across the desk/

PORFIRY: My dear, you also didn’t expect it. How your hands are shaking!

RASKOLNIKOV: You are also shaking, Porfiry Petrovich.

PORFIRY: I am shaking. I didn’t expect this!

RASKOLNIKOV: So, you won’t show me your surprise after all?

PORFIRY: You talk, but your teeth chatter. Goodbye.

RASKOLNIKOV: Rather, farewell!

PORFIRY: God willing. God willing! But, I will have to ask you a few f o r m a l questions at some point . . . so we’ll see each other soon.

RASKOLNIKOV: Porfiry Petrovich, please, forgive me. I got carried away.

PORFIRY: Don’t apologize. It’s nothing.

Me too. I . . . apologize . . . I apologize . . . . I can be pushy sometimes . . . . I apologize! See you soon.

RASKOLNIKOV: So, we’ll get to know each other really well?

PORFIRY: Yes, we’ll get to know each other really well.

RASKOLNIKOV: I would wish you good luck, but you see for yourself how ridiculous is your profession!

PORFIRY: Why ridiculous?

RASKOLNIKOV: I can only imagine how you tortured and investigated – psychologically – this poor Mikolka! Day and night, night and day, you hypnotized him: ‘You’re the killer, you’re the killer. . . . ’ And now, for the heck of it, you will be telling him: ‘You’re lying. You can’t be the killer! You can’t! You’re repeating someone else’s words.’

PORFIRY: So you heard what I just said: ‘You’re repeating someone else’s words’?

RASKOLNIKOV: How could I not?

PORFIRY: Well, well . . . . The incredibly clever mind of yours. You just hit the nail on the head . . . . Among writers, only Gogol had a similar skill.

RASKOLNIKOV: Yes, only Gogol.

PORFIRY: See you soon.

RASKOLNIKOV: See you soon.

PORFIRY: /To Mikolka, kicking him/

Get up.

/Opening door/

Get out.

/Eating soup/

Sit down.

You can go.

I’ll interrogate you some more. Talk.

MIKOLKA: I killed Alyona Ivanovna and her sister Lizaveta. I killed and robbed her.

SCENE X

“Surprise apologies”

MIESZCZYNIN: I apologize.

RASKOLNIKOV: What?

MIESZCZYNIN: I apologize . . .

RASKOLNIKOV: What for?

MIESZCZYNIN: Bad thoughts.

I feel bad. When you came over the other day, asking about the blood . . . . I had a suspicion. I felt weird that they let you go thinking you were drunk. I couldn’t sleep. We even came here yesterday, asking for you . . .

RASKOLNIKOV: Who came?

MIESZCZYNIN: I did. I misjudged you.

RASKOLNIKOV: So, it is you who live in that house?

MIESZCZYNIN: Yes, it was me who stood at the gates then . . . . Don’t you remember . . . . I feel really bad . . .

RASKOLNIKOV: So you told Porfiry Petrovich that I came over . . . ?

MIESZCZYNIN: What Porfiry Petrovich?

RASKOLNIKOV: The detective.

MIESCZANIN: It was me. The porters didn’t want to go, so I went to see him.

RASKOLNIKOV: Today?

MIESZCZYNIN: Just before you did. And I have heard everything, everything, that he said to you.

RASKOLNIKOV: Where? What? When?

MIESZCZYNIN: Behind the closed doors. I was hidden. I stood there during your entire conversation.

RASKOLNIKOV: What? So you were the surprise?

MIESZCZYNIN: When they bought you in, he told me to hide and stay hidden no matter what. And when Mikolka came, he let you go first and then, he told me to go. He also told me he would be questioning me later on . . .

RASKOLNIKOV: Did he question Mikolka in front of you as well?

MIESZCZYNIN: Right after he let you go, he let me go . . . . Please, forgive me for slandering you. . . .

RASKOLNIKOV: God will forgive you . . . Now, we’ll see who got what.

THE END OF ACT I

ACT II

SCENE XI

“Now, He Came”

SONIA: Do you know who killed her?

RASKOLNIKOV: I do.

SONIA: They caught him, didn’t they?

RASKOLNIKOV: No. They haven’t caught him.

SONIA: How do you know?

RASKOLNIKOV: Guess.

SONIA: But . . . me . . . why . . . are you scaring me like that?

RASKOLNIKOV: You can’t guess?

SONIA: N-no.

RASKOLNIKOV: Look carefully.

SONIA: Oh my God!

RASKOLNIKOV: You guessed.

SONIA: What did you do to yourself? What did you do to yourself?